I grew up watching and playing cricket. I’ve since fallen in love with baseball. They’re similar games: baseball was born from cricket. They both have subtlety, subplots, the ebb and flow of a long game. The games often contain something you’ve never seen before. I couldn’t find an interesting explanation of baseball for those who understand cricket — though I offer no promises of wikipedia’s (dull) comprehensiveness. This’ll be the first of two posts.

Getting out

You’ve read this far, so you must know some basics. There’s nine innings, each team bats in each inning, three outs and you change teams. When you’re out 27 times, it’s all over (unless it’s a draw – more on that later).

You can get out lots of different ways, just like cricket. The common ones are being caught, struck out, forced out, and tagged out. There’s also obscure ones – both cricket and baseball share rules around how long you have before you’re out for not batting in a timely fashion.

Australia playing the Seattle Mariners in 2009 in Peoria, Arizona. Australia was warming up for the World Baseball Classic, and the Mariners had just begun their Spring Training for the long season ahead. Australia won 11-9. The first game for Ken Griffey Jr with the Mariners in his second, unsuccessful stint with the team.

You get a strike against you as a batter when you swing the bat and miss, the ball passes through the strike zone without you hitting it, or you foul it off by hitting it outside the field of play (behind the lines that are on each side of the field, often marked at the ends by large yellow foul poles). You strike out when you do any of these three times – except you can’t get a third strike on a foul. Striking out is analogous to being bowled.

You get a free pass walk to first base if you’re hit by the ball (rather different to cricket). You also get a walk if you receive four pitches (so-called balls) that aren’t in the strike zone, and that you didn’t swing at. The strike zone is subtle: in the way LBW is subtle. It’s roughly knee height to just below the writing on the jersey, and roughly as wide as the home plate that sits on the ground.

You’re forced out when you have to advance to the next base, but you don’t make it. You must advance when you hit the ball into play (it always tippity run), or when you’re on a base and there’s a batter behind you who’s advancing to the base you’re on. Force outs typically happen by a fielder standing on the base you’re headed to and having the ball in their possession. It’s just like a keeper knocking the bails off in a run out, except it’s a run out where you were forced to run.

You’re tagged out when you’re touched by a fielder who’s holding the ball and you’re not safely on a base. This usually happens when you’ve decided to run to the next base when you weren’t forced to. This is a bit subtle: as a spectator, you have to know whether the runner is being forced or has chosen to run, so you know what to expect the fielder to do to get the out. This tagging the runner thing is something you don’t see in cricket.

There’s nine players, but sixteen 12th men

There are nine guys on the field when you’re fielding. One’s the pitcher, one’s the catcher (a wicketkeeper-like guy), and there’s seven fielders (position players). I’ll explain later where they all stand.

You can take any guy off the field, and replace him with any one of sixteen “12th men”. The catch is the guy that comes on the field really does replace the guy who left – he’s out of the game, and the new guy bats or pitches or both. The guy who left can’t come back – he’s a spectator until the next game. (I think this bears resemblance to the “super sub” they’ve experimented with a few times in cricket.)

In practice, there really isn’t sixteen 12th men. There are twenty-five guys on the team (“the 25 man roster”), but probably five or six of them won’t play on any given day. They’re usually pitchers who’ve pitched recently and are having a rest day, or are going to pitch tomorrow. And there’s always a backup catcher or two, which the team won’t bring into the game because they’re keeping him in reserve in case of injury (a bit like the backup goalkeeper in soccer).

So, really, you’re probably looking at ten guys who could come into the game: probably five or six pitchers, and four or five batters. In practice, you might typically see anywhere between zero and six of them. I’ll explain more on that topic later.

There’s an exception: in September, you’re allowed to have a 40 man roster. This is to allow teams to try out young players, and give the senior players some rest time before the postseason.

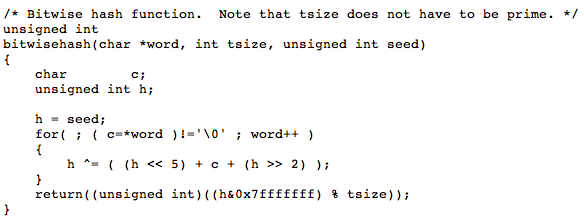

Batting order

Since there are nine guys per team, nine guys bat. They’re listed in a batting order, much like cricket. One bats at a time, there’s no non-striker’s end.

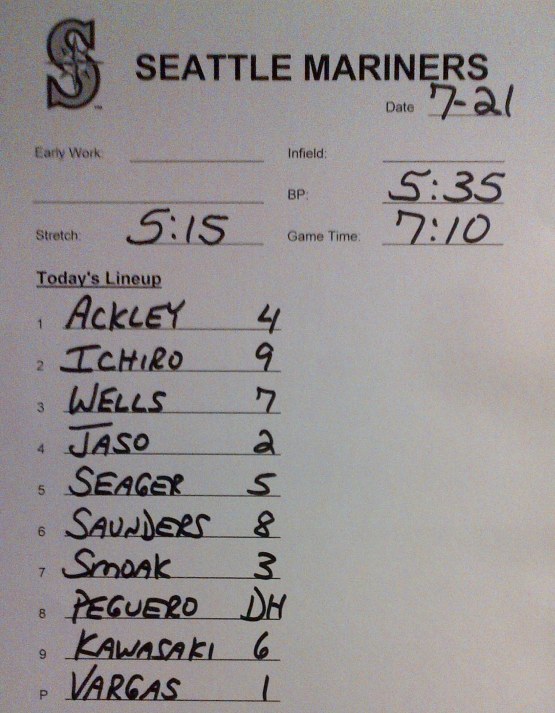

A lineup card that shows the batting order. These are exchanged between the teams before play — just like in cricket.

Once all nine guys have batted, they return to the top of the order, and the first guy bats again. There’s no limit on the number of times you bat – you just go around and around the batting order until the game is over.

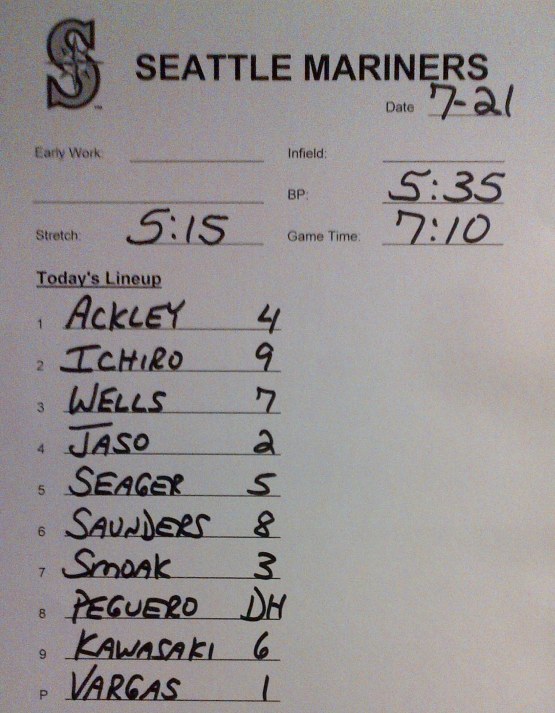

If you follow Major League Baseball, you’ll know there’s two Leagues: the American League (which has 14 teams) and the National League (which has 16 teams). Most of the time, teams from each league play only teams from that league. The major exception is the World Series – the final, championship games of the year, where the best team from the AL plays the best team from the NL to be crowned world champion. (There’s also this thing called interleague play, I’ll ignore that for now.)

Anyway, the point I’m getting to is this: the pitcher in an American League team doesn’t bat. So, instead of having nine players on the team, they actually have ten: there’s a guy called the “designated hitter” (or DH) who bats in place of the pitcher. Technically, the DH could bat for any other player, but it’s always the pitcher who doesn’t bat. The DH doesn’t field, he just sits around, and gets probably four or five chances to bat in the game.

In the National League, there’s no DH, and the pitchers bat. Pitchers bat about as well as Murali or Glenn McGrath. There are no all-rounders in baseball.

It’s odd that the two leagues have different rules. You’ll find baseball purists like talking about this. Try expressing a strong opinion on the topic.

As an aside, cricket has played around with a DH-like rule in domestic cricket competitions.

There’s a lot more baseball

Baseball purists are staggered that test cricket matches last for five days. That freaks them out. They’re used to games of baseball that are two or three or (wow, that was a long game) four hours.

I’m more freaked out by baseball: the Major League Baseball season has 162 games per team per year, and that’s not including the postseason (the finals). They play from April to September, and so most teams get maybe three or four days without a game each month. That’s a lot of baseball – there’s pretty much baseball on all day, every day – in fact, there’s 2430 games per season.

Seattle Mariners 2012 schedule. 162 games, always 81 at home and 81 away.

Because there’s so much baseball, you can get a ticket cheap. Only the Boston Red Sox routinely sell out their stadium. A cheap seat might be $6.

Failure is vastly more common

A few ducks in a row, and you’re probably going to get dropped from your cricket team. Not in baseball. Failure is expected, at least it’s ok for quite a while.

A very good batter in baseball does something useful about 35% of the time. The other 65% of the time, he’s out without doing anything useful – kind of like a duck in cricket. What’s something useful? Well, that could in the extreme be scoring runs – anywhere from one to four (the maximum you can score by hitting a home run when there’s three other guys on the three bases). At the other end, something useful is getting yourself to first base – so that the next guy can help you work on getting around to score a run.

Strangely, something useful can sometimes be getting out – in baseball, the ball isn’t dead when you’re out (unless it’s the third out, in which case the inning is over). If you hit the ball a long way, it’s caught, there’s a guy on second or third base, and he can run around to home, he’ll score a run.

Interestingly, while 35% success is very good, 20% success is very bad. This is a very fine line: succeed 1 in 3 times and you’re amazing, succeed 1 in 4 times and you are ok, and succeed 1 in 5 times and you’re a disaster.

The ball doesn’t bounce

I guess everyone knows the ball isn’t supposed to bounce in baseball. If it does, it’s referred to as a “pitch in the dirt”, which sort of means it was a useless yorker. Since there’s no stumps. there’s no point in trying to sneak the ball under the bat.

The ball not bouncing means that movement off the pitch isn’t a factor in baseball. Instead, baseball is about movement in the air and varying pitch speeds – which you also see in cricket. Movement in the air in baseball is imparted by spin and seams, which in turn is controlled by hand and finger position on the ball. Most good pitchers in baseball have at least three pitches that they throw – a fast ball (they’re pretty much all fast bowlers), and a couple of “off-speed pitches” (slower, deceptive pitches that move around or don’t look slow out of the hand).

Draws don’t happen

There are no draws or tied games. After nine innings, if the score is tied, the game goes into a tenth inning where both teams get a chance to bat. If it’s still tied, it’s time for the eleventh. A ten, eleven, or even twelve inning game is reasonably common. I was at a 15 inning game once, you won’t see that often. The longest professional game went 33 innings.

There’s no overs

Pitchers pitch until their manager decides to take him out of the game and replace him with another pitcher. Baseball has managers who’re in charge of team (rather than a head coach) – they really do make the decisions. You’ll see them come out and visit the pitcher, and let him know he’s done for the game.

A starting pitcher (the guy who starts the game) will typically pitch around 100 pitches, maybe up to 120 if he’s a strong, veteran pitcher. That’s between 17 and 20 overs in a spell! Of course, if he’s getting hit all over the place, anything’s possible – he might last as few as 20 or 30 pitches.

When a starting pitcher is replaced, he’ll typically be replaced with a guy who pitches harder and faster for fewer pitches – a so-called relief pitcher. You might see one to four relief pitchers in a game, depending on how many innings the starting pitcher pitched. Relief pitchers are quirky, and they often have specialty roles. For example, there’s often a guy who’s a left-hander who specializes in throwing at left-handers, and he may throw only one pitch in a game before being replaced (the call these guys LOOGYs, lefty one out guys).

A starting pitcher warms up for quite a while before the game, probably more than you’d typically see a bowler warm up. There’s really no looseners in baseball – pitchers pitch at their top speed from the first pitch. To start each inning, a pitcher gets precisely eight practice throws to their catcher before the first batter steps in to bat.

The catcher is closer

The catcher in baseball fields like a wicketkeeper standing up to a spin bowler. The difference is the pitcher is always a fast bowler, and he’s about 6 feet closer than a bowler in cricket. A typical pitcher throws between 88 and 100 miles per hour (as the ball leaves the hand). Only the fastest fast bowlers have ever hit 100 miles an hour.

The umpire (in black), catcher (in red), and batter (in blue) in close proximity. It’s normal for the umpire to lean on the catcher.

This means that the catcher has to know where the ball is going to go, because he hasn’t sufficient time to react to the pitch. If you watch carefully, you’ll see the catcher tell the pitcher what pitch he should throw before each pitch. He does this by wiggling his fingers between his legs. If the pitcher likes the idea, he’ll nod and pitch. If he doesn’t, he’ll shake his head and the catcher will try another idea. The signals tell the pitcher what kind of pitch to throw (speed and spin), and where to throw it (high or low, in or out).

I’ll share more thoughts on the (subtle?) differences between the games next time.